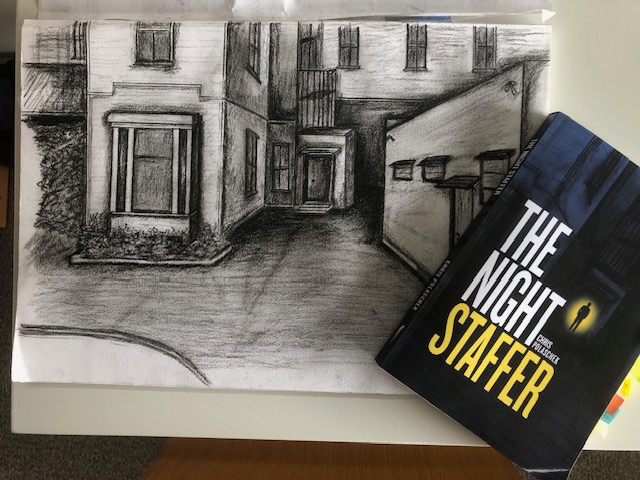

The Night Staffer Theme (1): Good vs Evil: Black, White or Grey?

Ever since I experienced being a night staffer in the year the Christchurch Boys Home closed (1987-8) I wanted to write this book. It was a totally new and fascinating time that I thought was worth sharing. Although I was in my early thirties when I started this work and had seen a bit of the world, including some of life's darker side, the experience was eye-opening and confronting. It certainly made me think about how we regard and treat our disadvantaged and challenging youth. These considerations became the underlying themes of the book. Over the next few weeks, I will explore the key themes further in a series of blogs.In a quiet period one evening as they await an admission, the night staff get into a dialogue about whether the incoming boy is good or evil. He comes from a criminal family so the debate that ensues is around whether he was socialized into the behaviour or if there is something more innate in his makeup and those of his family members. The discussion broadens into whether offending behaviour is learned or something more fundamental, a consequence of negative life experiences which have severely influenced the way the young person views their world. Are they victims or perpetrators? Should the focus of the State’s intervention be on meeting needs or holding the young person accountable for their deeds? Should there be a justice, (accountability and punishment) or welfare (treatment and care) approach? Or doesn’t it matter? Is the key issue that the community has a right to be safe? If the boys are committing crimes, the solution is that they need to be locked away in a place like the Boy's Home until they get the message their behaviour won’t be tolerated, and they change their ways.

The Night Staffer provides a glimpse underneath the behaviours into the lives of a group of young people who are representative of those who end up incarcerated. It enables, and hopefully encourages, the reader to reflect on the issues, contributing to that debate.

Many of the boys in the book have horrific early life experiences such as being maltreated, neglected, and abused. In a sense, the badness or the evilness has been done to them. Jai the main boy character has been deserted by his father and neglected by his mother. He has little to no connection or empathy with people. He does not trust adults or the agents of the State, such as social workers and Police. He has a casual attitude towards offending. He knows it’s wrong in his heart but like some of the other boys always has an excuse to justify why he does it. It is to survive on the run. Or the insurance company will pay so who really cares, or when he commits burglaries, it is from the rich so they can afford it. It’s all a bit of harmless fun. Jai is like other kids identified broadly as ‘waifs and strays.’ These are young people who have become disconnected from society and may have few personal resources, intellectual or otherwise, on which to build a future. So, they drift from day to day doing what is necessary to survive.

There are other boys who have committed serious violent offences and caused real physical harm. For them, violence is a tool, a means to an end and the victim is of no regard. We see the bullies and kingpins use violence because it works for them. A few of the portraits are of boys who are presented as being close to evil, like Gerhart the skinhead. He is belligerent, racist, and dangerous. Although we are not told much about Gerhart’s background, he is a member of a gang. Participation requires that he behave in certain ways and demonstrate group-conforming attitudes. Like other gang affiliates, he is making choices that are about being included and accepted into the group. It would appear this is meeting a need for him, the need to belong. We do not know for sure, but it is reasonable to assume it might be something that was previously missing from his life. However, there is no suggestion he is remotely interested in changing. In fact, when he is given the opportunity, he is quick to spew his hateful rhetoric. He is articulate and sufficiently intelligent to make cohesive arguments. Is it this confirmed behaviour that makes him evil? Is he so far gone that he is now irretrievable?

Another group that makes up the residential population are young people who have significant developmental impairment or delay, or who have low intellectual function. For example, there is a young person who has sexually abused his much younger sister. He is very immature, unworldly, a ‘fish out of water’ in the residence. There is another who is in residence because he acts on his uncontrolled sexual desires making him a risk to others. He masturbates in front of other boys because he does not comprehend social constraints. Pedophilic behaviour or the inability to control sexual desires makes them an ongoing long-term risk that will extend into adulthood. From a victim’s perspective, their acts are evil in their consequences because they cast a shadow that will last a lifetime.

The above boys are an example of an obvious deficit, namely low intellectual function, but there are more insidious deficits that are less visible but still very consequential on behaviour. On the surface, some of the young people in the residence appeared to be average teenagers with a few behavioural issues but if we dig deeper, we suspect that undetected neglect and/or abuse mean they have been handicapped physically and emotionally from the time they started their developmental journey. From early on they will have viewed the world around them quite differently from those who experienced a more ‘normal’ upbringing. They may be continually experiencing substantial levels of anxiety, fear, or emotional insecurity. These days we would consider such factors as contributing to low-level comorbid psychiatric dysfunction. Even when these issues have not been formally diagnosed, and they generally were not a consideration for the Boy's Home population back in the 1980s, it is obvious that they would have impacted developmental progress. Take Jai for example. He has had to fend for himself for a large part of his life because of his mother's disengagement from her responsibilities and this has contributed to a strong sense that adults are at best unreliable and uncaring, and at worst may also pose a threat. Most of the time he presents as a confident self-reliant young person but substance abuse, a bit of dope and booze, have become part of his coping mechanisms.

Whether the boys are seen as unfortunates, mental health clients or just plain bad’ makes a significant difference to staff attitudes towards the individuals and the group. This is exacerbated by the ‘one size fits all’ nature of the residence which makes it hard to take a more nuanced approach to how the group is managed. In The Night Staffer, we see the various teams in the residence tend to take a particular perspective that helps them make sense of the environment. One team takes zero tolerance towards poor behaviour so tends to be more custodial and risk management in focus. Possibly this is even a ‘blaming’ and accountability focus. Another is viewed by the boys as wishy-washy, but one suspects they are more accommodating because they have strong empathy, giving precedence to the view most of the boys are victims needing care and protection.

Sometimes members within the same team have conflicting views. This is true of the night staffers. Mr. Rogers considers the older boys to be ‘ratbags’ but there are a few younger ones that he has known for some time that he sees as care and protection cases, and he is more inclined to put an effort into these young people. Ted believes that no matter what, community rights override the rights of the individual and the boys need to learn that lesson. He does not deny that they have faced difficulties but believes that some are ‘too far gone’ to be retrieved, especially where the whole family has been in residence or prison. Wyatt seems to sit on the fence. He’s relatively new so he doesn’t know. He sees both sides. In some families, one child offends and another does not, so behaviours are not always predetermined by experiences. In his head, he seems to lean more towards seeing the boys as victims. It may be that he is influenced by the fact that he likes Jai and so is more willing to take a sympathetic view. However, when it comes to his actions, especially when controlling the group, risky and dangerous behaviours are managed quickly and effectively, with a clear emphasis on safety first.

In a lot of ways, this discussion is most pertinent if we are considering adolescents because they sit at the crossroads between childhood dependence and adult self-responsibility. Some of the boys in residence are big and mature and in a physical sense they pose the same threat as an adult. To all intents and purposes, they are regarded as adults. Most of the boys know right from wrong, sufficient to be able to make better choices. Not all of course, some only have the most rudimentary understanding of the morality of what they do or they may not have the ability to control their impulses. For others, they will develop it in time but at the point at which they are in residence, they have not sufficiently matured because of developmental delays. Regardless of where they might sit in terms of their physical development, from what we now know, it may take seven or eight more years beyond their time in residence for their brains to fully mature. Hindsight is a great thing.

So, what is the nature of evil? Is it in the behaviour or in the outcome? Is it a choice a person makes, or is it a consequence of life experiences? The Night Staffer does not pretend to answer those questions, but it contributes information and perspectives for the reader to consider. It is a debate that, like a pendulum, swings back and forward.

Post Views : 200